Excess savings occur when households and businesses accumulate more capital than is invested, leading to decreased aggregate demand and slower economic growth. Secular stagnation describes a prolonged period of negligible or negative real interest rates, where insufficient demand inhibits full employment and investment despite low borrowing costs. Explore the dynamics between excess savings and secular stagnation to understand their impact on long-term economic trends.

Why it is important

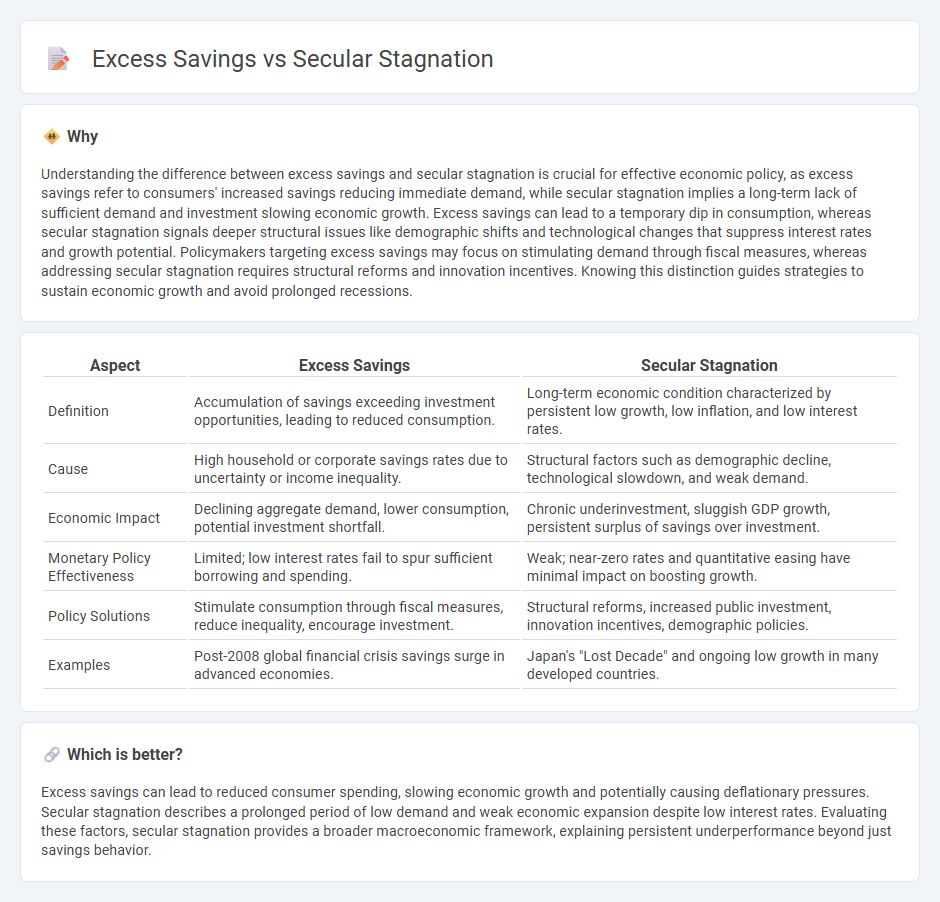

Understanding the difference between excess savings and secular stagnation is crucial for effective economic policy, as excess savings refer to consumers' increased savings reducing immediate demand, while secular stagnation implies a long-term lack of sufficient demand and investment slowing economic growth. Excess savings can lead to a temporary dip in consumption, whereas secular stagnation signals deeper structural issues like demographic shifts and technological changes that suppress interest rates and growth potential. Policymakers targeting excess savings may focus on stimulating demand through fiscal measures, whereas addressing secular stagnation requires structural reforms and innovation incentives. Knowing this distinction guides strategies to sustain economic growth and avoid prolonged recessions.

Comparison Table

| Aspect | Excess Savings | Secular Stagnation |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Accumulation of savings exceeding investment opportunities, leading to reduced consumption. | Long-term economic condition characterized by persistent low growth, low inflation, and low interest rates. |

| Cause | High household or corporate savings rates due to uncertainty or income inequality. | Structural factors such as demographic decline, technological slowdown, and weak demand. |

| Economic Impact | Declining aggregate demand, lower consumption, potential investment shortfall. | Chronic underinvestment, sluggish GDP growth, persistent surplus of savings over investment. |

| Monetary Policy Effectiveness | Limited; low interest rates fail to spur sufficient borrowing and spending. | Weak; near-zero rates and quantitative easing have minimal impact on boosting growth. |

| Policy Solutions | Stimulate consumption through fiscal measures, reduce inequality, encourage investment. | Structural reforms, increased public investment, innovation incentives, demographic policies. |

| Examples | Post-2008 global financial crisis savings surge in advanced economies. | Japan's "Lost Decade" and ongoing low growth in many developed countries. |

Which is better?

Excess savings can lead to reduced consumer spending, slowing economic growth and potentially causing deflationary pressures. Secular stagnation describes a prolonged period of low demand and weak economic expansion despite low interest rates. Evaluating these factors, secular stagnation provides a broader macroeconomic framework, explaining persistent underperformance beyond just savings behavior.

Connection

Excess savings contribute to secular stagnation by reducing aggregate demand, leading to persistently low interest rates and subdued economic growth. This imbalance between savings and investment creates a liquidity trap where central banks struggle to stimulate the economy despite low borrowing costs. As a result, prolonged insufficient demand hinders capital expenditure and productivity improvements, reinforcing the cycle of sluggish expansion.

Key Terms

Aggregate Demand

Secular stagnation theory attributes prolonged low economic growth to insufficient aggregate demand caused by factors such as demographic shifts, technological changes, and increased savings outpacing investment opportunities. Excess savings reduce consumption and investment, leading to a persistent output gap and downward pressure on interest rates, which monetary policy alone may fail to correct. Explore the interplay between secular stagnation and excess savings to understand their impact on aggregate demand and economic policy.

Interest Rates

Secular stagnation theory suggests that persistently low interest rates result from a chronic excess of savings over investment, suppressing economic growth. Excess savings drive down natural interest rates, creating a liquidity trap where monetary policy loses effectiveness. Explore the dynamics between secular stagnation and excess savings to understand the impact on global interest rate trends.

Investment

Secular stagnation theory suggests a chronic deficiency in investment demand despite abundant savings, leading to prolonged low interest rates and sluggish economic growth. Excess savings can result in underutilized capital, reducing incentives for businesses to invest in new projects or innovation. Explore the dynamics between secular stagnation and excess savings to understand their impact on global investment trends.

Source and External Links

Will secular stagnation return? The stakes for current economic debates and fiscal policy - Secular stagnation is a real, long-term economic condition marked by a persistent shortfall in aggregate demand compared to productive capacity, driven largely by structural factors like income inequality concentrating wealth among high savers, thereby reducing overall spending growth.

Secular stagnation - Secular stagnation refers to a condition of negligible or no economic growth over the long term in a market economy, first identified by Alvin Hansen in 1938 as a post-Great Depression risk stemming from limited investment opportunities and structural economic shifts.

Secular Stagnation - Definition, Problems, Solutions - Economist Larry Summers explained secular stagnation as a chronic imbalance where excess saving over investment reduces demand, growth, and inflation, often fueled by rising inequality and asset accumulation, recommending government fiscal spending on infrastructure and green energy as solutions.

dowidth.com

dowidth.com